LAUGHING AND TOLERANCE

by Bernard BOUTON / France

Among the thousands of cartoons we could see in the exhibitions, in the books or on the internet, some are only for fun, others are made for the purpose of sharing ideas. We want to take a closer look at cartoons with a “message”.

There are cartoons that talk about human rights, about peace, about tolerance. For example, “tolerance” was the theme of the Universal Tolerance Cartoon Festival, in October 2013 and hundreds of works were received.

The question is : how did the cartoonists deal with the subject “tolerance” ? What was the strategy followed by the cartoonist to ensure making a suitable artwork ? Did they make a cartoon funny or not funny, appropriate …or not.

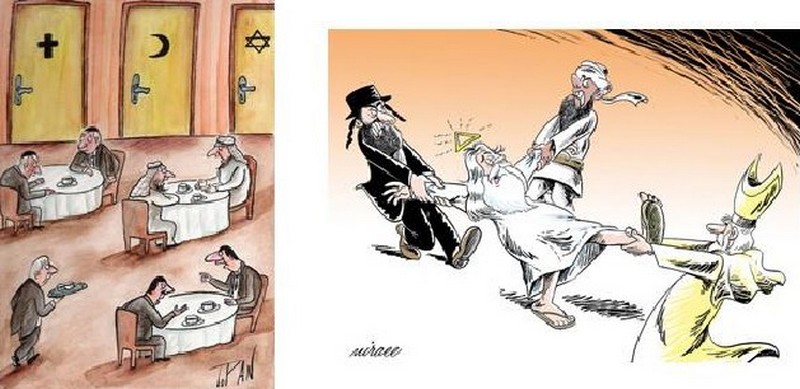

We noticed that some cartoons show tolerant characters (see below on the left), while others show intolerant people (on the right).

Huey Nguyenhuu Samuel Mwamkinga

Huey Nguyenhuu Samuel Mwamkinga

Then, we will call these two categories “positive cartoon” for the first one, and “critical cartoon” for the second one.

Generally the cartoons of the second category are more comical than those of the first category ; because it is easier to laugh about bad people !

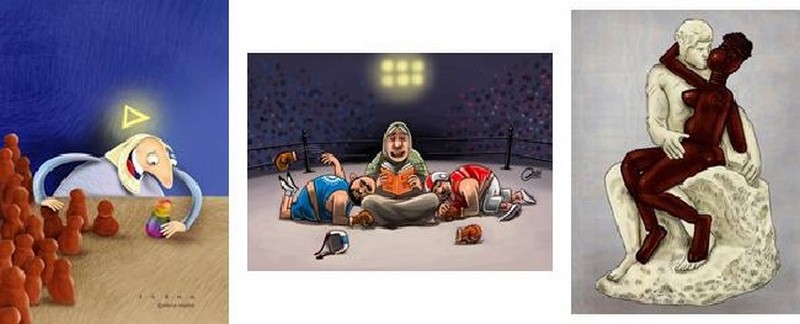

However we can laugh with a “positive cartoon” when we appreciate a clever idea from the cartoonist (see below) :

Elena Ospina Ali Paknahad Kfir Weizman

Elena Ospina Ali Paknahad Kfir Weizman

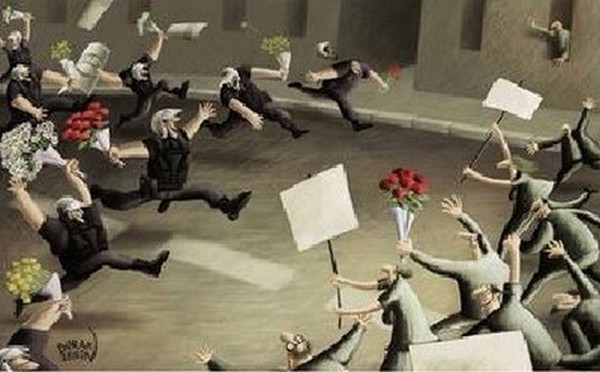

We can also laugh with a “positive cartoon” when there is an exaggeration, an excessiveness in the drawing :

Burak Ergin

Burak Ergin

.

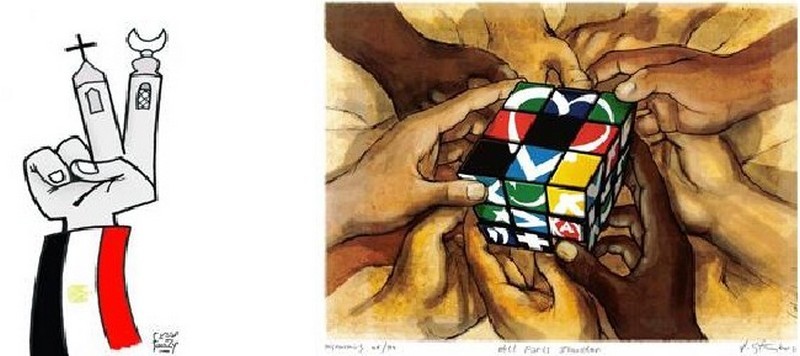

Among the “positive cartoons” some are simply illustrations, filled with naive optimism :

Fawzy Morsy Vladimir Stankovski

Fawzy Morsy Vladimir Stankovski

.

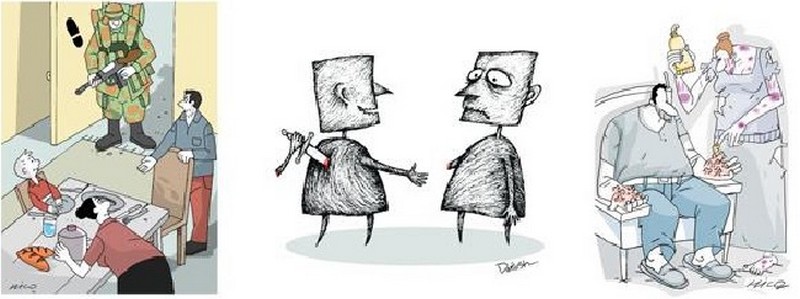

Others are very moving because in the cartoon we see a tolerant person, who knows how to forgive those who have injured him (like Nelson Mandela did it).

Hicabi Demirci Dariush Ramezani Hicabi Demirci

Hicabi Demirci Dariush Ramezani Hicabi Demirci

.

But let us come back to the second category ; the cartoons are funny because the intolerant characters are ridiculous :

Cristian Topan Ali Miraee

Cristian Topan Ali Miraee

.

On the right : the representatives of three religions fighting for control of the same God (!) On the left : separated toilets for separated religions (!)

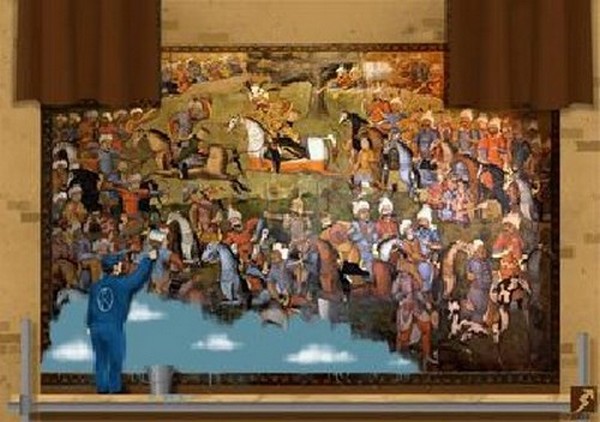

The awarded cartoon for the first prize belongs to the first category and it is a very clever cartoon (see below) :

Saman Torabi

Saman Torabi

.

In fact, it is a cartoon against war, not against intolerance, but when you are against war, you should be tolerant …The jury must have thought that … Of course the jury was tolerant … The role of the jury is another topic that we could discuss in more detail later in another text.

Summing up, on the topic “tolerance”, cartoons are divided into two general categories according to their viewpoint, critical or optimism. Similar analysis was conducted for many other themes. Cartoons for peace – or critical against war,

Cartoons for human rights – or critical against countries in which there is no respect for human rights, etc …

Recently we were asked for cartoons about the theme “charity” ; in the call, the organizer said : “We’re looking for cartoons that celebrate charity, but also cartoons that criticize humanity’s lack of charity”

However, for many other themes, cartoons do not fit into these two categories ; for example, for the theme “Brainwashing”, the cartoonist had to use another strategy to make a suitable artwork. This is another issue that could be discussed in a further text.

Bernard BOUTON

(author of the article is renowned French cartoonist and the Secretary General of FECO)

*****